Jelly Roll Morton

Jelly Roll Morton | |

|---|---|

Morton c. 1927 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe |

| Born | c. September 20, 1890[1] New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 10, 1941 (aged 50) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, ragtime, blues,[2] Dixieland[3] |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, arranger |

| Instrument | Piano |

| Years active | 1904–1941 |

| Labels | Victor, Gennett |

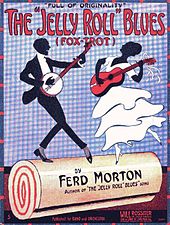

Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe (né Lemott,[4] later Morton; c. September 20, 1890 – July 10, 1941), known professionally as Jelly Roll Morton, was an American blues and jazz pianist, bandleader, and composer of Louisiana Creole descent.[5] Morton was jazz's first arranger, proving that a genre rooted in improvisation could retain its essential characteristics when notated.[6] His composition "Jelly Roll Blues", published in 1915, was one of the first published jazz compositions. He also claimed to have invented the genre.[7]

Morton also wrote "King Porter Stomp", "Wolverine Blues", "Black Bottom Stomp", and "I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say", the last being a tribute to New Orleans musicians from the turn of the 20th century.

Morton's claim to have invented jazz in 1902 was criticized.[5] Music critic Scott Yanow wrote, "Jelly Roll Morton did himself a lot of harm posthumously by exaggerating his worth ... Morton's accomplishments as an early innovator are so vast that he did not really need to stretch the truth."[5] Gunther Schuller says of Morton's "hyperbolic assertions" that there is "no proof to the contrary" and that Morton's "considerable accomplishments in themselves provide reasonable substantiation.”[8]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Morton was born Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe (or Lemott), into the Creole community[9] in the Faubourg Marigny neighborhood of New Orleans around 1890; he claimed to have been born in 1884 on his WWI draft registration card in 1918. Both parents traced their Creole ancestry four generations to the 18th century.[10] Morton's birth date and year of birth are uncertain, given that no birth certificate was ever issued for him. The law requiring birth certificates for citizens was not enforced until 1914.[11] His parents were Martin-Edouard Joseph Lamothe, also known as Edward Joseph Lamothe, a bricklayer and occasional trombonist,[12] and Louise Hermance Monette, a domestic worker. His parents were never legally married and his father left his mother when Morton was around three years old. After his mother married William Mouton in 1894, Ferdinand adopted his stepfather's surname, anglicizing it to Morton, adapting "Ferd" as an unofficial forename. Ferd had two sisters, one of whom, Eugénie, married Ignace Colas, in 1913.[13]

Career

[edit]

At the age of fourteen, Morton began as a piano player in a brothel.[14] He often sang smutty lyrics and used the nickname "Jelly Roll", which was African-American slang for female genitalia.[15][16] While working there, he was living with his churchgoing great-grandmother. He convinced her that he worked as a night watchman in a barrel factory. After Morton's grandmother found out he was playing jazz in a brothel, she disowned him for disgracing the Lamothe name.[17] "When my grandmother found out that I was playing jazz in one of the sporting houses in the District, she told me that I had disgraced the family and forbade me to live at the house. She told me that devil music would surely bring about my downfall..."[17] The cornetist Rex Stewart recalled that Morton had chosen "the nom de plume 'Morton' to protect his family from disgrace if he was identified as a whorehouse 'professor'."[15]

Around 1904, Morton started touring in the US South, working in minstrel shows such as Will Benbow's Chocolate Drops,[18] gambling, and composing. His songs "Jelly Roll Blues", "New Orleans Blues", "Frog-I-More Rag", "Animule Dance", and "King Porter Stomp" were composed during this period. Stride pianists James P. Johnson and Willie "The Lion" Smith saw him perform in Chicago in 1910 and New York City in 1911.[19]

In 1912–14, Morton toured with his girlfriend Rosa Brown as a vaudeville act before living in Chicago for three years. By 1914, he was putting his compositions on paper. In 1915 "Jelly Roll Blues" was one of the first jazz compositions to be published. Jelly Roll Morton was employed by Ben Shook Jr. around 1916. Shook was associated with a Jubilee club led by Mabel Lewis, a contralto singer and former member of the original Fisk University Jubilee Singers[citation needed]. In 1917 he went to California with bandleader William Manuel Johnson and Johnson's sister Anita Gonzalez, born Bessie Julia Johnson. Morton's tango "The Crave" was popular in Hollywood.[20] He was invited to perform at the Hotel Patricia nightclub in Vancouver, Canada. Author Mark Miller described his arrival as "an extended period of itinerancy as a pianist, vaudeville performer, gambler, hustler, and, as legend would have it, pimp".[21] Morton returned to Chicago in 1923 to claim authorship of "The Wolverines", which had become popular as "Wolverine Blues". He released the first of his commercial recordings, first as piano rolls, then on record, both as a piano soloist and with jazz bands.[22]

In 1926, Morton signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company, giving him the opportunity to bring a well-rehearsed band to play his arrangements in the Victor recording studios in Chicago. These recordings by Jelly Roll Morton and His Red Hot Peppers included Kid Ory, Omer Simeon, George Mitchell, Johnny St. Cyr, Barney Bigard, Johnny Dodds, Baby Dodds, and Andrew Hilaire.[23]

After Morton moved to New York City, he continued to record for Victor.[24] Although he had trouble finding musicians who wanted to play his style of jazz, he recorded with Omer Simeon, George Baquet, Albert Nicholas, Barney Bigard, Russell Procope, Lorenzo Tio and Artie Shaw, the trumpeters Ward Pinkett, Bubber Miley, Johnny Dunn and Henry "Red" Allen, Sidney Bechet, Paul Barnes, Bud Freeman, Pops Foster, Paul Barbarin, Cozy Cole, and Zutty Singleton. His New York sessions failed to produce a hit.[25]

Due in part to the Great Depression, RCA Victor did not renew Morton's recording contract for 1931. He continued playing in New York but struggled financially. He briefly had a radio show in 1934, then toured in a burlesque band. In 1935, his 30-year-old composition "King Porter Stomp", arranged by Fletcher Henderson, became Benny Goodman's first hit and a swing standard, but Morton received no royalties from the recordings.[26]

Music Box interviews

[edit]In 1935, Morton moved to Washington, D.C., to become the manager and piano player at a bar called, at various times, the Music Box, Blue Moon Inn, and Jungle Inn, at 1211 U Street NW in Shaw, an African-American neighborhood. Morton was master of ceremonies, bouncer, and bartender. The club owner allowed her friends free admission and drinks, which prevented Morton from making the business a success.[27] During Morton's brief residency at the Music Box, the folklorist Alan Lomax heard him play. In May 1938, Lomax invited Morton to record music and interviews for the Library of Congress. The sessions were intended to be a short interview with musical examples for researchers at the Library of Congress, but the sessions expanded to over eight hours, with Morton talking and playing piano. Lomax conducted longer interviews, taking notes but not recording.[28] Lomax was interested in Morton's days in Storyville, New Orleans, and the ribald songs of the time. Although reluctant to record these, Morton obliged Lomax. Because of the suggestive nature of the songs, some of the Library of Congress recordings were not released until 2005.[28]

In these interviews, Morton claimed to have been born in 1885. Morton scholars, such as Lawrence Gushee, say that Morton was aware that if he had been born in 1890, he would have been too young to claim to be the inventor of jazz. However, Morton may not have known his actual birthdate, and there remains the possibility that he was telling the truth. He said Buddy Bolden played ragtime but not jazz, a view not accepted by some of Bolden's contemporaries in New Orleans. The contradictions may stem from different definitions of "ragtime" and "jazz".

Stabbing, later life, and death

[edit]In 1938, Morton was stabbed by a friend of the Music Box's owner and suffered wounds to the head and chest. A nearby whites-only hospital refused to treat him, as the city had racially segregated facilities. He was transported to a black hospital farther away. When he was in the hospital, doctors left ice on his wounds for several hours before attending to the injury. His recovery from his wounds was incomplete, and thereafter he was often ill and became short of breath easily. After this incident, his wife Mabel demanded they leave Washington.[27]

Worsening asthma sent him to a hospital in New York for three months. He continued to suffer from respiratory problems when he travelled to Los Angeles with the intent to restart his career. He died on July 10, 1941, after an eleven-day stay in Los Angeles County General Hospital. He was generally believed to be 50 years old. According to the jazz historian David Gelly in 2000, Morton's arrogance and "bumptious" persona alienated so many musicians that few of them attended his funeral.[29]

An article about the funeral in the August 1, 1941, issue of DownBeat reported that his pallbearers were Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, Fred Washington, and Ed Garland. It noted that Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford were absent, though both were appearing in Los Angeles at the time.[30] Mercer Ellington, Duke Ellington's son, did attend the funeral. The article was reproduced in Mister Jelly Roll, a 1950 biography of Morton by Alan Lomax.

Personal life

[edit]Morton married Mabel Bertrand, a showgirl, in November 1928 in Gary, Indiana.

He was a "very devout Catholic", according to Anita Gonzales, his long-term companion. His gravesite features a large rosary rather than any music imagery.[31]

Form and compositions

[edit]Morton's piano style was formed from early secondary ragtime and "shout", which also evolved separately into the New York school of stride piano. Morton's playing was also close to barrelhouse, which produced boogie-woogie.[32]

Morton often played the melody of a tune with his right thumb, while sounding a harmony above these notes with the fingers of the right hand. This could add a rustic or "out-of-tune" sound due to the playing of a diminished 5th above the melody. This technique may still be recognized as belonging to New Orleans. Morton also walked in major and minor sixths in the bass, instead of tenths or octaves. He played basic swing rhythms with both the left and the right hand.

Several of Morton's compositions were musical tributes to himself, including "Winin' Boy", "The Jelly Roll Blues" (subtitled "The Original Jelly-Roll"); and "Mr. Jelly Lord". In the big-band era, his "King Porter Stomp", which Morton had written decades earlier, was a big hit for Fletcher Henderson and Benny Goodman; it became a standard covered by most other swing bands of that time. Morton claimed to have written some tunes that were copyrighted by others, including "Alabama Bound"[33] and "Tiger Rag". "Sweet Peter", which Morton recorded in 1926, appears to be the source of the melody of the hit song "All of Me", which was credited to Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons in 1931.

His musical influence continues in the work of Dick Hyman[34] and Reginald Robinson.[35]

Legacy

[edit]In 2013, Katy Martin published an article arguing that Alan Lomax's book of interviews put Morton in a negative light.[36] Martin disagreed that Morton was an egotist.

In being called a supreme egotist, Jelly Roll was often a victim of loose and lurid reporting. If we read the words that he himself wrote, however, we learn that he almost had an inferiority complex and said that he created his own style of jazz piano because 'All my fellow musicians were much faster in manipulations, I thought than I, and I did not feel as though I was in their class.' So he used a slower tempo to permit flexibility through the use of more notes, a pinch of Spanish to give a number of right seasoning, the avoidance of playing triple forte continuously, and many other points.[37]

Awards and honors

[edit]- The Music Box interviews were released posthumously as boxed set and won two Grammy Awards.[28]

- During the same year, Morton was honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

- Morton was posthumously nominated in 1992 for the Tony Award for Best Original Score for the musical depicting his life, Jelly's Last Jam.

- Morton was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and was elected as a charter member of the Gennett Records Walk of Fame.

- He was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2008.[38]

Discography

[edit]- 1923/24 (Milestone, 1923–24)

- Red Hot Peppers Session: Birth of the Hot, The Classic Red Hot Peppers Sessions (RCA Bluebird, 1926–27)

- The Pearls (RCA Bluebird, 1926–1939)

- Jazz King of New Orleans (RCA Bluebird, 1926–30)

- Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, Vols. 1–8 (8-CD Box Set) (Rounder, 2005)

Representation in other media

[edit]- Jelly Roll Morton's Last Night at the Jungle Inn: An Imaginary Memoir (1984), by the ethnomusicologist and folklorist Samuel Charters, embellishing Morton's early stories about his life.[39]

- In the chorus of "And It Stoned Me," the opening track of his seminal 1970 album Moondance, Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison sings "And it stoned me to my soul, stoned me just like Jelly Roll, and it stoned me." The reference is thought to be to the childhood memory of listening to his father's Morton recordings.[40]

- Clarence Williams III portrays Jelly Roll Morton in The Legend of 1900.

- Jelly's Last Jam is a musical with a book by George C. Wolfe, lyrics by Susan Birkenhead, and music by Jelly Roll Morton and Luther Henderson.[7]

- In season 1, episode 3 of AMC's Interview with the Vampire, at around 1917 in Storyville, Morton (portrayed by Kyle Roussel) is the featured entertainment for the fictional brothel called the Fair Play Saloon, that later becomes the Azalea Hall, owned by the vampire Louis de Pointe du Lac. Several decades later in 2022, Louis claims in his interview with Daniel Molloy, that it was Lestat's improvisation of Morton's music that contributes to the recording of Wolverine Blues.

- Morton is covered extensively in the 2011 book by Peggy Hicks, The Ghost of the Cuban Queen Bordello, detailing the life of Bessie Julia Johnson, also known as Anita Gonzales. Teenager Morton first knew Bessie/Anita as a prostitute in Storyville, then in 1917 he followed her to Las Vegas, Nevada, where she was a madam. They toured the US, buying a house together in Los Angeles. They moved to Jerome, Arizona, where she operated a bordello. They married in late 1918, quarreled frequently, moved around, and divorced. He traveled alone to Chicago. They kept in contact over the years, with Morton borrowing money. Morton sought her out at the end of his life, and died in her arms.[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Other dates of birth attributed to Morton include October 20, 1890 Archived November 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and September 13, 1884, the latter of which Morton gave on his WWI draft registration, making him six years older than he is believed to have actually been. Archived February 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ruggiero, Bob (March 19, 2024). "The "Original" Jelly Roll and the Dirty Early Blues". Houston Press. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ https://www.jazzhistorytree.com/new-orleans-dixieland-revival/

- ^ Biography Archived November 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, doctorjazz.co.uk. Accessed July 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c Yanow, Scott. "Jelly Roll Morton". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Giddins, Gary; DeVeaux, Scott (2009). Jazz. New York City: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06861-0.

- ^ a b Green, Jesse (February 22, 2024). "'Jelly's Last Jam' Review: A Musical Paradise, Even in Purgatory - Did Jelly Roll Morton "invent" jazz, as he claimed? A sensational Encores! revival offers a postmortem prosecution of one of the form's founding fathers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Schuller, Gunther (1986). The History of Jazz. Volume 2. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-19-504043-0.

- ^ John Szwed, "Doctor Jazz", booklet in Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, Rounder (2005), p. 3.

- ^ Detailed information, complete with charts, and drawing on the research of Lawrence Gushee, is available from Peter Hanley's Jelly Roll Morton: An Essay in Genealogy (2002) Archived February 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hanley, Jelly Roll Morton: An Essay in Genealogy. His baptismal certificate lists his date of birth as October 20, 1890, but Hanley prefers September 20, 1890. John Szwed, on the other hand, prefers 1895. See "Doctor Jazz" in Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings (Rounder Records, 2005), p. 4.

- ^ Musical Gumbo - The Music of New Orleans. W.W. Norton. 1993. ISBN 9780393034684. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ Ignace Colas Biodata Archived July 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, doctorjazz.co.uk. Accessed July 18, 2023.

- ^ Oakley, Giles (1997). The Devil's Music. Da Capo Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-306-80743-5.

- ^ a b Stewart, Rex (1991). Boy Meets Horn. Claire P. Gordon, ed. University of Michigan Press. Cited in Levin, Floyd (2000). Classic Jazz: A Personal View of the Music and the Musicians. University of California Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9780520213609. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Major, Clarence (1994). Juba to Jive: The Dictionary of African-American Slang. New York: Penguin. p. 256. ISBN 9780140513066.

- ^ a b "The Devil's Music: 1920s Jazz". PBS. February 2, 2000. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Jelly Roll Morton: On the Road, 1905–1917" Archived January 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. DoctorJazz.co.uk. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's blues : the life, music, and redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Da Capo. ISBN 9780306812095. Retrieved April 27, 2020 – via archive.org.

- ^ "Jelly Rolled into Vancouver". CBC Radio 2. March 31, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ Reich and Gaines (2003). Jelly's Blues. Da Capo Press. pp. 70–98. ISBN 9780306812095.

- ^ Reich and Gaines (2003). Jelly's Blues. Da Capo Press. pp. 114–127. ISBN 9780306812095.

- ^ Reich and Gaines (2003). Jelly's Blues. Da Capo Press. pp. 132–135. ISBN 9780306812095.

- ^ Reich and Gaines (2003). Jelly's Blues. Da Capo Press. pp. 132–144. ISBN 9780306812095.

- ^ Reich and Gaines (2003). Jelly's Blues. Da Capo Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 9780306812095.

- ^ a b "U Street Jazz – Performers – Prominent Jazz Musicians: Their Histories in Washington, D.C." Gwu.edu. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Library of Congress Recordings of Jelly Roll Morton Win at Grammys". Library of Congress. Loc.gov. January 14, 2006. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Gelly, David (2000). Icons of Jazz. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay. ISBN 1-57145-268-0.

- ^ "Bury Jelly Roll Morton on Coast". DownBeat. 8 (15): 13. August 1, 1941. Retrieved April 13, 2024. Additional Morton material on pp. 1 & 4 of this issue.

- ^ Gioia, Ted (April 2017). "Duke Ellington's Faith". First Things. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Jelly Roll Morton". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ Giles Oakley (1997). The Devil's Music. Da Capo Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-306-80743-5.

- ^ Carr, Ian; Fairweather, Digby; Priestley, Brian (2004). The Rough Guide to Jazz. Rough Guides. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-84353-256-9. Archived from the original on July 28, 2024. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (November 28, 2000). "The Man Who Made Jazz Hot; 60 Years After His Death, Jelly Roll Morton Gets Respect". New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Martin, Katy (February 2013). "The Preoccupations of Mr. Lomax, Inventor of the "Inventor of Jazz"". Popular Music and Society. 36 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1080/03007766.2011.613225. hdl:1808/4202. S2CID 191490584.

- ^ Quoted in John Szwed, Dr. Jazz. Book accompanying the box set Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax, Rounder 11661-188-BK01 (2005)

- ^ "Louisiana Music Hall of Fame". LouisianaMusicHallOfFame.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Charters, Samuel Barclay (1984). Jelly Roll Morton's Last Night at the Jungle Inn: An Imaginary Memoir. Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2805-6.

- ^ "Song Review 'And it stoned Me'". AllMusic. allmusic.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Hicks, Peggy (2011). The Ghost of the Cuban Queen Bordello. Peggy Hicks. ISBN 9-7805-7807-3439.

Sources

[edit]- Dapogny, James. Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton: The Collected Piano Music. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

- The Devil's Music: 1920s Jazz. PBS.

- Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. p. 486.

- "Ferdinand J. 'Jelly Roll' Morton". A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (1988), pp. 586–587.

- "Jelly". Time, March 11, 1940.

- Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Kenneth. Jazz, a History of America's Music. Random House.

Further reading

[edit]- Dapogny, James (1982). Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton: The Collected Piano Music. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Gushee, Lawrence (2010). Pioneers of Jazz : The Story of the Creole Band. Oxford University Press.

- Lomax, Alan (1950, 1973, 2001). Mister Jelly Roll. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22530-9.

- Martin, Katy (2013). "The Preoccupations of Mr. Lomax, Inventor of the 'Inventor of Jazz.'" Popular Music and Society 36.1 (February 2013), pp. 30–39. DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2011.613225.

- Pareles, Jon (1989). "New Orleans Sauce for Jelly Roll Morton: 'He Was the First Great Composer and Jazz Master', Tribute to Jelly Roll Morton." New York Times, 1989, sec. Arts.

- Pastras, Phil (2001). Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West. University of California Press.

- Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2004). Jelly's Blues: The Life, Music, and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- Russell, William (1999). Oh Mister Jelly! A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook, Copenhagen: Jazz Media ApS.

- Schafer, William J (2008). “The Original Jelly Roll Blues”. Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84451-394-9. This biography offers clear contemplation of Morton and his music according to the book preface by Howard Mandel.

- Stone, Jonathan (2021), "Inventing Jazz: Jelly Roll Morton and the Sonic Rhetorics of Hot Musical Performance", Listening to the Lomax Archive, University of Michigan Press, pp. 115–158, doi:10.3998/mpub.9871097, ISBN 9780472902446, JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.9871097, S2CID 234248416

- Szwed, John. "Doctor Jazz" (2005). Liner notes to Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax. Rounder Boxed Set. 80-page illustrated monograph. This book-length essay is also available without illustrations at Jazz Studies Online: John Szwed, Doctor Jazz: Jelly Roll Morton.

- Wald, Elijah (2024). Jelly Roll Blues - Censored Songs & Hidden Histories. Hachette Books ISBN 9780306831409

- Wright, Laurie (1980). Mr. Jelly Lord. Storyville Publications.

External links

[edit]- Ferd 'Jelly Roll' Morton

- Genealogy of Jelly Roll Morton

- Jelly Roll Morton Music (73:73) on YouTube

- William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection

- Jelly Roll Morton recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings

- Free scores by Jelly Roll Morton at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Jelly Roll Morton at the Red Hot Jazz Archive; biography with audio files of many of Morton's historic recordings

- 1890 births

- 1941 deaths

- 20th-century American conductors (music)

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American pianists

- 20th-century American jazz composers

- 20th-century African-American musicians

- African-American Catholics

- African-American conductors (music)

- African-American jazz composers

- African-American jazz pianists

- American jazz bandleaders

- American jazz pianists

- American male conductors (music)

- American male jazz composers

- American male jazz pianists

- Burials at Calvary Cemetery (Los Angeles)

- Dixieland jazz musicians

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- Jazz arrangers

- Louisiana Creole people

- Ragtime composers

- Red Hot Peppers members

- American vaudeville performers

- Victor Records artists

- 19th-century Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- 20th-century Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members