University of Texas at Austin

| |

| Latin: Universitas Texana[1] | |

Former names | The University of Texas (1881–1967)[2] |

|---|---|

| Motto | Disciplina Praesidium Civitatis (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Education is the Guardian of the State"[a][3] |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | September 15, 1883 |

Parent institution | University of Texas System |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $19.72 billion (2023) (UT Austin only)[4] $44.97 billion (2023) (system-wide)[5] |

| Budget | $3.97 billion (FY2024)[4] |

| President | Jay Hartzell[6] |

| Provost | Rachel D. Mersey |

Academic staff | 3,254 (fall 2022)[7] |

Administrative staff | 11,645 (2015)[8] |

| Students | 52,384 (fall 2022)[9] |

| Undergraduates | 42,444 (fall 2023)[7] |

| Postgraduates | 9,469 (fall 2023)[7] |

| Location | , , United States 30°17′06″N 97°44′06″W / 30.285°N 97.735°W |

| Campus | Large city[10], 431 acres (1.74 km2) |

| Newspaper | The Daily Texan |

| Colors | Burnt orange and white[11] |

| Nickname | Longhorns |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS - SEC[12] |

| Mascot | |

| Website | utexas |

| |

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 52,384 students as of fall 2022, it is also the largest institution in the system.[13]

The university is a major center for academic research, with research expenditures totaling $1.06 billion for the 2023 fiscal year.[14] It joined the Association of American Universities in 1929. The university houses seven museums and seventeen libraries, including the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and the Blanton Museum of Art, and operates various auxiliary research facilities, such as the J. J. Pickle Research Campus and the McDonald Observatory.

UT Austin's athletics constitute the Texas Longhorns. The Longhorns have won four NCAA Division I National Football Championships, six NCAA Division I National Baseball Championships, thirteen NCAA Division I National Men's Swimming and Diving Championships, and the school has claimed more titles in men's and women's sports than any other member in the Big 12.

As of 2020,[update] 13 Nobel Prize winners, 25 Pulitzer Prize winners, three Turing Award winners, two Fields Medal recipients, two Wolf Prize winners, and three Abel Prize winners have been affiliated with the school as alumni, faculty members, or researchers. The university has also been affiliated with three Primetime Emmy Award winners, and as of 2021, its students and alumni have earned a total of 155 Olympic medals.[15]

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]The idea of a public university in Texas was first mentioned in the 1827 constitution of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, which promised public education in the arts and sciences under Title 6, Article 217, but no action was taken.[16] After Texas gained independence from Mexico in 1836, the Constitution of the Republic emphasized Congress's duty, in Section 5 of its General Provisions, to establish a general system of education when circumstances allowed.[17]

After Texas was annexed, the Seventh Texas Legislature passed O.B. 102 on February 11, 1858, allocating $100,000 in United States bonds from the Compromise of 1850 for the University of Texas.[18][19] The Civil War delayed fund repayment, leaving the university with only $16,000 by 1865.[20] Nevertheless, the Texas Constitution of 1876 reaffirmed the mandate to establish "The University of Texas" by popular vote.[21]

On March 30, 1881, the Texas legislature organized the structure of the university and called for a popular vote to determine its location.[22] Austin was chosen as the site with 30,913 votes, while Galveston was designated for the medical department.[23][24] On November 17, 1882, the cornerstone of the Old Main building was laid at the original "College Hill" location, and University President Ashbel Smith expressed optimism about Texas's untapped resources.[25] The University of Texas officially opened its doors on September 15, 1883.[26]

Expansion and growth

[edit]The old Main Building of the university was built in a Victorian-Gothic style and served as the central point of the campus's 40-acre (16 ha) site, and was used for nearly all purposes. But by the 1930s, discussions arose about the need for new library space, and the Main Building was razed in 1934, despite the objections of many students and faculty. The modern-day tower and Main Building were constructed in its place.[27][28]

In 1916, a contentious dispute erupted between Texas Governor James E. Ferguson and the University of Texas over faculty appointments. Ferguson's attempt to influence these appointments led to a retaliatory veto of the university's budget, jeopardizing its operations. Subsequently, Ferguson was impeached by the Texas House of Representatives, convicted by the Senate on charges including misapplication of public funds, and removed from office.[29]

In 1921, the legislature appropriated $1.35 million for the purchase of land next to the main campus. However, expansion was hampered by the restriction against using state revenues to fund construction of university buildings as set forth in Article 7, Section 14 of the Constitution. With the completion of Santa Rita No. 1 well[30] and the discovery of oil on university-owned lands in 1923, the university added significantly to its Permanent University Fund. The additional income from Permanent University Fund investments allowed for bond issues in 1931 and 1947, which allowed the legislature to address funding for the university along with the Agricultural and Mechanical College (now known as Texas A&M University). With sufficient funds to finance construction on both campuses, on April 8, 1931, the Forty Second Legislature passed H.B. 368.[31] which dedicated the Agricultural and Mechanical College a 1/3 interest in the Available University Fund,[32] the annual income from Permanent University Fund investments.

In 1929, the University of Texas was inducted into the Association of American Universities.[33]

During World War II, the University of Texas was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[34] Additionally, to facilitate the wartime effort, academic calendars were compressed, allowing for accelerated graduation.[35]

After Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, Houston, Texas, area teen Marion Ford had been accepted to become one of the first Black attendees. In an interview with a reporter he announced his desire to try-out for the football team. The Ford Crisis would begin and all Black admissions at the time were rescinded until policy could be drawn up.[36]

In the fall of 1956, the first Black students entered the university's undergraduate class.[37] Black students were permitted to live in campus dorms, but were barred from campus cafeterias.[37] The University of Texas integrated its facilities and desegregated its dormitories in 1965.[38] UT, which had had an open admissions policy, adopted standardized testing for admissions in the mid-1950s, at least in part as a conscious strategy to minimize the number of Black undergraduates, given that they were no longer able to simply bar their entry after the Brown decision.[39]

Following growth in enrollment after World War II, the university unveiled an ambitious master plan in 1960 designed for "10 years of growth" that was intended to "boost the University of Texas into the ranks of the top state universities in the nation."[40] In 1965, the Texas Legislature granted the university Board of Regents to use eminent domain to purchase additional properties surrounding the original 40 acres (160,000 m2). The university began buying parcels of land to the north, south, and east of the existing campus, particularly in the Blackland neighborhood to the east and the Brackenridge tract to the southeast, in hopes of using the land to relocate the university's intramural fields, baseball field, tennis courts, and parking lots.[40]

On March 6, 1967, the Sixtieth Texas Legislature changed the university's official name from "The University of Texas" to "The University of Texas at Austin" to reflect the growth of the University of Texas System.[41]

1966 shooting

[edit]

On August 1, 1966, Texas student Charles Whitman barricaded the observation deck in the tower of the Main Building. Armed with multiple firearms, he killed 14 people on campus, 11 from the observation deck and below the clocks on the tower, and three more in the tower, as well as wounding two others inside the observation deck. The massacre ended when Whitman was shot and killed by police after they breached the tower.

After the Whitman event, the observation deck was closed until 1968 and then closed again in 1975 following a series of suicide jumps during the 1970s. In 1999, after installation of security fencing and other safety precautions, the tower observation deck reopened to the public. There is a turtle pond park near the tower dedicated to those affected by the tragedy.

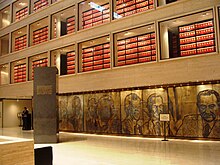

The first presidential library on a university campus was dedicated on May 22, 1971, with former President Johnson, Lady Bird Johnson and then-President Richard Nixon in attendance. Constructed on the eastern side of the main campus, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum is one of 13 presidential libraries administered by the National Archives and Records Administration.

A statue of Martin Luther King Jr. was unveiled on campus in 1999 and subsequently vandalized.[42] By 2004, John Butler, a professor at the McCombs School of Business suggested moving it to Morehouse College, a historically black college, "a place where he is loved".[42]

Recent history

[edit]The University of Texas at Austin has experienced a wave of new construction recently with several significant buildings. On April 30, 2006, the school opened the Blanton Museum of Art.[43] In August 2008, the AT&T Executive Education and Conference Center opened, with the hotel and conference center forming part of a new gateway to the university. Also in 2008, Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium was expanded to a seating capacity of 100,119, making it the largest stadium (by capacity) in the state of Texas at the time.[44]

On Tuesday, September 28, 2010, a shooting occurred at the Perry–Castañeda Library (PCL) where student Colton Tooley, armed with an AK-47, fired shots on his walk from Guadalupe Street to the library's front entrance. The student ascended to the sixth floor, before killing himself. No one else was injured, except for one sprained ankle suffered by a female student fleeing the scene.[45]

In early 2020, following a major outbreak of the new coronavirus, the university restricted travel to Wuhan province in China, aligning with the U.S. Department of State's recommendation.[46] By March 17, 2020, then-UT President Gregory L. Fenves announced a transition to online classes for the rest of the spring semester after 49 confirmed COVID-19 cases emerged from students' travels to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, during spring break.[47] Throughout the summer, the university reported over 400 cases and its first COVID-19-related death, a custodial worker.[48][49]

The fall 2020 semester consisted of a majority of online courses through platforms like Zoom. On August 6, 2020, UT Austin initiated plans for free COVID-19 tests for all students. UT Austin returned to primarily in-person classes and campus activities for the fall 2021 semester, implementing safety protocols like testing requirements and vaccination incentives to ensure a safe return amid the ongoing pandemic.[50]

In 2024, after four years of test-optional admissions for undergraduate applications due to the COVID-19 pandemic, standardized testing scores were once again made a mandatory part of admissions, beginning with applications for the fall 2025 semester.[51] Jay Hartzell commented that the SAT and ACT standardized exams were "a proven differentiator that is in each student's and the University's best interest."[51]

On April 2, 2024, the University of Texas at Austin announced additional adjustments in compliance with Senate Bill 17,[52] particularly in response to a letter from March 26, 2024 from Texas State Senator Brandon Creighton,[53] which led to the layoff of approximately 60 individuals, most of whom formerly worked in DEI-related programs, and the elimination of the newly-renamed Division of Campus and Community Engagement.[54] Students, faculty, staff, and outside critics denounced the university's over-compliance with the anti-DEI law, since the university had already been compliant since January 1, 2024.[55][56] At a UT Austin Faculty Council meeting on April 15, 2024, in response to mounting criticism, President Jay Hartzell stated the additional changes were made in response to the threats from the Republican-led State Legislature and the University of Texas System Board of Regents, and to restore "confidence" in the university, reacting to changing tides in public opinion towards higher education amongst Republicans.[57] The university's Division of Campus and Community Engagement operated the University of Texas-University Charter School, a charter school system with 23 campuses across Texas, until the closure on April 2, 2024, leading the charter school to be moved to the College of Education.[58]

2024 pro-Palestinian protests

[edit]

On February 4, 2024, a Palestinian-American student at a pro-Palestinian protest at the campus was stabbed, receiving non-life-threatening injuries.[59][60] The attacker used a racial slur against the protestors and the attack was investigated as a hate crime.[61][62][63] A month later the attacker was indicted by a grand jury on an aggravated assault with a deadly weapon charge but was not charged with any additional hate crime charge.[64]

A large student and faculty Pro-Palestinian protest occurred on April 24, 2024, demanding a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas War and that the university divest from companies profiting from Israel's actions.[65] The protests occurred amidst the ongoing nationwide demonstrations on college campuses.[66][67]

In response, the university, under the explicit direction of President Hartzell,[68][69] requested the assistance of the Austin Police Department (APD) and the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), in coordination with Texas Governor Greg Abbott, in an attempt to quell said protests and an "occupation" of the university,[70][71] in contrast to free speech on campus laws praised by Abbott and the university in prior years.[72] The deployment of multiple police units led to the confirmed arrest of 57 protesters, including a photojournalist for Fox 7 Austin, with several more detained.[73][74][75][76][77] Charges were then dismissed against 46 protesters the next day, leading to their subsequent release,[78][65][79] with the charges against the remaining 11 protesters dropped on April 26, 2024.[80]

This decision received sharp backlash, including from general faculty, staff, students, several Democratic legislators for the region, and First Amendment advocacy groups,[81][82] including an official statement from the UT Faculty Council Executive Committee denouncing it,[83] in part due to the extreme, chaotic, and violent police response that ensued and alleged violations of First Amendment rights.[84][73] The university additionally set new rules for protests on campus, such as banning masks and face coverings and instituting a 10 PM curfew for all protests, directly contradicting prior guidelines.[85] Initially, the university told students and faculty that arrested protestors would no longer be allowed on campus, but retracted the statement two hours later, stating that they would be allowed "academic" access, only to then announce a change to full access for university affiliates.[86] Additionally, the university temporarily suspended the student organization that organized the protests, the Palestine Solidarity Committee.[87] Travis County Attorney Delia Garza stated that the way that the university handled the protests put a strain on the local criminal justice system, specifically reprimanding the sending of protestors to jail for low-level charges.[88]

A report later released by the UT Austin Committee of Counsel on Academic Freedom and Responsibility (CCAFR) on July 17, 2024 found that UT Austin administrators violated its own institutional rules in clear disregard of freedom of speech and expression protections.[89]

Campus

[edit]The university's property totals 1,438.5 acres (582.1 ha), comprising the 423.5 acres (171.4 ha) for the Main Campus in central Austin and the J. J. Pickle Research Campus in north Austin and the other properties throughout Texas. The main campus has 150 buildings totaling over 18,000,000 square feet (1,700,000 m2).

One of the university's most visible features is the Beaux-Arts Main Building, including a 307-foot (94 m) tower designed by Paul Philippe Cret.[90] Completed in 1937, the Main Building is in the middle of campus. The tower usually appears illuminated in white light in the evening but is lit burnt orange for various special occasions, including athletic victories and academic accomplishments; conversely, it is darkened for solemn occasions.[91] At the top of the tower is a carillon of 56 bells, the largest in Texas. Songs are played on weekdays by student carillonneurs,[92] in addition to the usual pealing of Westminster Quarters every quarter-hour between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m.[93] In 1998, after the installation of security and safety measures, the observation deck reopened to the public indefinitely for weekend tours.[94]

The university's seven museums and seventeen libraries hold over nine million volumes, making it the seventh-largest academic library in the country.[95] The holdings of the university's Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center include one of only 21 remaining complete copies of the Gutenberg Bible and the first permanent photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras, taken by Nicéphore Niépce.[96] The newest museum, the 155,000-square-foot (14,400 m2) Blanton Museum of Art, is the largest university art museum in the United States and hosts approximately 17,000 works from Europe, the United States, and Latin America.[97][98] The Perry–Castañeda Library, which houses the central University Libraries operations and the Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection, is at the heart of campus. The Benson Latin American Collection holds the largest collection of Latin American materials among US university libraries,[99] and maintains substantial digital collections.[100]

The University of Texas at Austin has an extensive tunnel system that links the buildings on campus. Constructed c. 1928 under the supervision of UT engineering professor Carl J. Eckhardt Jr., then head of the physical plant, the tunnels have grown along with the campus.[101] They measure approximately six miles in length.[102][103] The tunnel system is used for communications and utility service. It is closed to the public and guarded by silent alarms. Since the late 1940s, the university has generated its own electricity. Today its natural gas cogeneration plant has a capacity of 123 MW. The university also operates a TRIGA nuclear reactor at the J. J. Pickle Research Campus.[104][105]

The university continues to expand its facilities on campus. In 2010, the university opened the state-of-the-art Norman Hackerman building (on the site of the former Experimental Sciences Building) housing chemistry and biology research and teaching laboratories. In 2010, the university broke ground on the $120 million Bill & Melinda Gates Computer Science Complex and Dell Computer Science Hall and the $51 million Belo Center for New Media, both of which are now complete.[106][107] The new LEED gold-certified, 110,000-square-foot (10,000 m2) Student Activity Center (SAC) opened in January 2011, housing study rooms, lounges and food vendors. The SAC was constructed as a result of a student referendum passed in 2006 which raised student fees by $65 per semester.[108] In 2012, the Moody Foundation awarded the College of Communication $50 million, the largest endowment any communication college has received, so naming it the Moody College of Communication.

The university operates two public radio stations, KUT with news and information, and KUTX with music, via local FM broadcasts as well as live streaming audio over the Internet. The university uses CapMetro to provide bus transportation for students around the campus on the UT Shuttle system and throughout Austin, and UT students, faculty, and staff with an active UT ID card are able to ride public transportation without paying a fare.[109]

Organization and administration

[edit]

The university contains eighteen colleges and schools and one academic unit, each listed with its founding date:[110]

- Cockrell School of Engineering (1894)

- Dell Medical School (2013)

- College of Education (1905)

- College of Fine Arts (1938)

- College of Liberal Arts (1883)

- College of Natural Sciences (1883)

- College of Pharmacy (1893 in Galveston, moved to Austin 1927)

- Continuing Education (1909)

- Graduate Studies (1910)

- Jackson School of Geosciences (2005)

- LBJ School of Public Affairs (1970)

- McCombs School of Business (1922)

- Moody College of Communication (1965)

- School of Architecture (1948)

- School of Information (1948)

- School of Law (1883)

- School of Nursing (1976)

- School of Undergraduate Studies (2008)

- Steve Hicks School of Social Work (1950)

Academics

[edit]

The University of Texas at Austin offers more than 100 undergraduate and 170 graduate degrees. In the 2009–2010 academic year, the university awarded a total of 13,215 degrees: 67.7% bachelor's degrees, 22.0% master's degrees, 6.4% doctoral degrees, and 3.9% Professional degrees.[111]

In addition, the university has nine honors programs, eight of which span a variety of academic fields: Liberal Arts Honors, the Business Honors Program, the Turing Scholars Program in Computer Science, Engineering Honors, the Dean's Scholars Program in Natural Sciences, the Health Science Scholars Program in Natural Sciences, the Polymathic Scholars Program in Natural Sciences, and the Undergraduate Nursing Honors Program in School of Nursing. The ninth is the Plan II Honors Program, a rigorous interdisciplinary program that is a major in and of itself.[112] Many Plan II students pursue a second major, often participating in another department's honors program in addition to Plan II.[113] The university also offers programs such as the Freshman Research Initiative and Texas Interdisciplinary Plan.[114]

Admissions

[edit]Undergraduate

[edit]| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 28.8 ( |

| Yield rate | 47.7 ( |

| Test scores middle 50% | |

| SAT Total | 1230–1480 (among 56% of FTFs) |

| ACT Composite | 29–34 (among 26% of FTFs) |

The University of Texas at Austin encourages applicants to submit SAT/ACT scores, but it is not required.[117] However, for students applying for admission from fall 2025 onwards, submission of SAT/ACT scores is mandatory as part of their undergraduate admission application.[118] As of 2011, the university was one of the most selective universities in the region. Relative to other universities in the state of Texas, UT Austin was second to Rice University in selectivity according to a Business Journal study weighing acceptance rates and the mid-range of the SAT and ACT. The University of Texas at Austin was ranked as the 18th most selective in the South.[119]

As a state public university, UT Austin was subject to Texas House Bill 588, which guaranteed Texas high school seniors graduating in the top 10% of their class admission to any public Texas university. A new state law granting UT Austin (but no other state university) a partial exemption from the top 10% rule, Senate Bill 175, was passed by the 81st Legislature in 2009. It modified this admissions policy by limiting automatically admitted freshmen to 75% of the entering in-state freshman class, starting in 2011. The university will admit the top one percent, the top two percent and so forth until the cap is reached; the university currently admits the top 6 percent.[120] Furthermore, students admitted under Texas House Bill 588 are not guaranteed their choice of college or major, but rather only guaranteed admission to the university as a whole. Many colleges, such as the Cockrell School of Engineering, have secondary requirements that must be met for admission.[121]

For others who go through the traditional application process, selectivity is deemed "more selective" according to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and by U.S. News & World Report.[122][123] For fall 2017, 51,033 applied and 18,620 were accepted (36.5%), and of those accepted, 45.2% enrolled.[124] Among freshman students who enrolled in fall 2017, SAT scores for the middle 50% ranged from 570 to 690 for critical reading and 600–710 for math.[124] ACT composite scores for the middle 50% ranged from 26 to 31.[124] In terms of class rank, 74.4% of enrolled freshmen were in the top 10% of their high school classes and 91.7% ranked in the top quarter.[124] For fall 2019, 53,525 undergraduate students applied, 17,029 undergraduate students were admitted, and 8,170 undergraduate students enrolled in the university full or part time, making the acceptance rate 31.8% and enrollment rate 48% overall.[125] In the 2020–2021 academic year, 79 freshman students were National Merit Scholars.[126]

| 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 66,043 | 57,241 | 53,525 | 50,575 | 51,033 | 47,511 |

| Admits | 18,989 | 18,291 | 17,029 | 19,482 | 18,620 | 19,182 |

| Admit rate | 28.8 | 32.0 | 31.8 | 38.5 | 36.5 | 40.4 |

| Enrolled | 9,060 | 8,459 | 8,170 | 8,960 | 8,381 | 8,719 |

| Yield rate | 47.7 | 46.2 | 48.0 | 46.0 | 45.0 | 45.5 |

| ACT composite* (out of 36) |

29–34 (26%†) |

26–33 (47%†) |

27–33 (54%†) |

27–33 (56%†) |

26–33 (65%†) |

26–32 (64%†) |

| SAT composite* (out of 1600) |

1230–1480 (56%†) |

1220–1450 (79%†) |

1240–1470 (79%†) |

1230–1480 (78%†) |

1230–1460 (73%†) |

— |

| * middle 50% range † percentage of first-time freshmen who chose to submit | ||||||

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[131] | 46 |

| U.S. News & World Report[132] | 30 (tie) |

| Washington Monthly[133] | 98 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[134] | 41 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[135] | 45 |

| QS[136] | 66 |

| THE[137] | 50 |

| U.S. News & World Report[138] | 56 (tie) |

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) was ranked 32nd among all universities in the U.S. and 9th among public universities according to U.S. News & World Report's 2024 rankings.[132] Internationally, UT Austin was tied for 56th in the 2024 "Best Global Universities" ranking by U.S. News & World Report, 45th in the world by Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) in 2024, 52nd worldwide by Times Higher Education World University Rankings (2024), and 66th globally by QS World University Rankings (2024). UT Austin was also ranked 35th in the world by the Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) in 2024.[139]

The University of Texas at Austin is considered to be a "Public Ivy"—a public university that provides an Ivy League collegiate experience at a public school price, having been ranked in virtually every list of "Public Ivies" since Richard Moll coined the term in his 1985 book Public Ivies: A Guide to America's best public undergraduate colleges and universities. The seven other "Public Ivy" universities, according to Moll, were the College of William & Mary, Miami University, the University of California, the University of Michigan, the University of North Carolina, the University of Vermont, and the University of Virginia.[140]

The Accounting and Latin American History programs are consistently ranked top in the nation by the U.S. News & World Report college rankings, most recently in their 2023 and 2021 editions, respectively.[141][142] More than 50 other science, humanities, and professional programs rank in the top 25 nationally.[143] The College of Pharmacy is listed as the third-best in the nation and The School of Information (iSchool) is sixth-best in Library and Information Sciences.[143] Among other rankings, the School of Social Work is 7th, the Jackson School of Geosciences is 8th for Earth Sciences, the Cockrell School of Engineering is tied for 10th-best (with the undergraduate engineering program tied for 11th-best in the country), the Nursing School is tied for 13th, the University of Texas School of Law is 15th, the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs is 7th, and the McCombs School of Business is tied for 16th-best (with the undergraduate business program tied for 5th-best in the country).[143]

The University of Texas School of Architecture was ranked second among national undergraduate programs in 2012.[144]

A 2005 Bloomberg survey ranked the school 5th among all business schools and first among public business schools for the largest number of alumni who are S&P 500 CEOs.[145] Similarly, a 2005 USA Today report ranked the university as "the number one source of new Fortune 1000 CEOs".[146] A "payback" analysis published by SmartMoney in 2011 comparing graduates' salaries to tuition costs concluded the school was the second-best value of all colleges in the nation, behind only Georgia Tech.[147] A 2013 College Database study found that UT Austin was 22nd in the nation in terms of increased lifetime earnings by graduates.[148]

Research

[edit]

UT Austin is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity."[123] For the 2014–2015 cycle, the university was awarded over $580 million in sponsored projects,[149][150] and has earned more than 300 patents since 2003.[151] The University of Texas at Austin houses the Office of Technology Commercialization, a technology transfer center which serves as the bridge between laboratory research and commercial development. In 2009, the university created nine new start-up companies to commercialize technology developed at the university and has created 46 start-ups in the past seven years. License agreements generated $10.9 million in revenue for the university in 2009.[151] In January 2020, the University of Texas Austin's Texas Innovation Center was established to provide support for startups.[152]

Research at UT Austin is largely focused in the engineering and physical sciences,[153] and the university is a world-leading research institution in fields such as computer science.[154] Energy is a major research thrust, with federally funded projects on biofuels,[155] battery and solar cell technology, and geological carbon dioxide storage,[156] water purification membranes, among others. In 2009, the University of Texas founded the Energy Institute, led by former Under Secretary for Science Raymond L. Orbach, to organize and advance multi-disciplinary energy research.[157] In addition to its own medical school, it houses medical programs associated with other campuses and allied health professional programs, as well as major research programs in pharmacy, biomedical engineering, neuroscience, and others.

In 2010, the University of Texas at Austin opened the $100 million Dell Pediatric Research Institute to increase medical research at the university and establish a medical research complex, and associated medical school, in Austin.[158][159]

The university operates several major auxiliary research centers. The world's third-largest telescope, the Hobby–Eberly Telescope, and three other large telescopes are part of the university's McDonald Observatory, 450 miles (720 km) west of Austin.[160][161] The university manages nearly 300 acres (120 ha) of biological field laboratories, including the Brackenridge Field Laboratory in Austin. The Center for Agile Technology focuses on software development challenges.[162] The J.J. Pickle Research Campus (PRC) is home to the Texas Advanced Computing Center which operates a series of supercomputers, such as Ranger (from 2008 to 2013[163]), Stampede (2013–2017[164]), Stampede2 (since 2017[165]), and Frontera (since 2019).[166] The Pickle campus also hosts the Microelectronics Research Center which houses micro- and nanoelectronics research and features a 15,000 square foot (1,400 m2) cleanroom for device fabrication.

Founded in 1946, the university's Applied Research Laboratories at the PRC has developed or tested the vast majority of the Navy's high-frequency sonar equipment. In 2007, the Navy granted it a research contract funded up to $928 million over ten years.[167][168] The Institute for Advanced Technology, founded in 1990 and located in the West Pickle Research Building, supports the U.S. Army with basic and applied research in several fields.

The Center for Transportation Research is a nationally recognized research institution focusing on transportation research, education, and public service. Established in 1963 as the Center for Highway Research, its projects address virtually all aspects of transportation, including economics, multimodal systems, traffic congestion relief, transportation policy, materials, structures, transit, environmental impacts, driver behavior, land use, geometric design, accessibility, and pavements.[169]

In 2013, the University of Texas at Austin announced the naming of the O'Donnell Building for Applied Computational Engineering and Sciences. The O'Donnell Foundation of Dallas, headed by Peter O'Donnell and his wife, Edith Jones O'Donnell, has given more than $135 million to the university between 1983 and 2013. University president William C. Powers declared the O'Donnells "among the greatest supporters of the University of Texas in its 130-year history. Their transformative generosity is based on the belief in our power to change society for the better."[170] In 2008, O'Donnell pledged $18 million to finance the hiring of university faculty members undertaking research in mathematics, computers, and multiple scientific disciplines; his pledge was matched by W. A. "Tex" Moncrief Jr., an oilman and philanthropist from Fort Worth.[171] In addition, UT Austin and Amazon established a new science hub in 2023.[172] [173]

The University of Texas at Austin Marine Science Institute is located on the Gulf coast in Port Aransas. Established in 1941, UTMSI was the first permanent marine research facility in the state of Texas and has since contributed significantly to our understanding of marine ecosystems. Research at the Marine Science Institute ranges from locally-important work on mariculture and estuarine ecosystems to the investigation of global issues in marine science, from the Arctic to the tropics.

Endowment

[edit]

The University of Texas System is entitled to at least 30% of the distributions from the Permanent University Fund (PUF), with over $33 billion in assets as of year-end 2021.[174][175] The University of Texas System gets two-thirds of the Available University Fund (the name of the annual distribution of PUF's income), and the Texas A&M University System gets the other third. A regental policy[176] requires at least 45 percent of UT System's share of this money go to the University of Texas at Austin for "program enrichment". By taking two-thirds and multiplying it by 45 percent, UT gets 30 percent, which is the minimum amount of AUF income that can be distributed to the school under current policies. The Regents, however, can decide to allocate additional amounts to the university. Also, the majority of the University of Texas system share of the AUF is used for its debt service bonds, some of which were issued for the benefit of the Austin campus.[177] The Regents can change the 45 percent minimum of the University of Texas System share that goes to the Austin campus at any time, although doing so might be difficult politically.

Proceeds from lands appropriated in 1839 and 1876, as well as oil monies, comprise the majority of PUF. At one time, the PUF was the chief source of income for Texas' two university systems, the University of Texas System and the Texas A&M University System; today, however, its revenues account for less than 10 percent of the universities' annual budgets. This has challenged the universities to increase sponsored research and private donations. Privately funded endowments contribute over $2 billion to the university's total endowment.

The University of Texas System also has about $22 billion of assets in its General Endowment Fund.[178]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[179] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 37% | ||

| Hispanic | 26% | ||

| Asian | 23% | ||

| Other[b] | 5% | ||

| Black | 6% | ||

| Foreign national | 4% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[c] | 23% | ||

| Affluent[d] | 77% | ||

Student profile

[edit]For fall 2023, the university enrolled 42,444 undergraduate students and 9,469 graduate students, bringing the total student count to 51,913. Out-of-state students accounted for 10% of the undergraduate student body, and international students comprised 9.6% of the total student body.[180] Out-of-state and international students comprised 9.1% of the undergraduate student body and 20.1% of the total student body, with students from all 50 states and more than 120 foreign countries—most notably, the Republic of Korea, followed by the People's Republic of China, India, Mexico, and Taiwan.[181]

For fall 2015, the undergraduate student body was 48.9% male and 51.1% female.[182] In 2022, the three most popular undergraduate majors were Biology/Biological Sciences, Psychology, and Computer and Information Sciences. For graduate studies, the top choices were Business Administration and Management, Accounting, and Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods.[183]

Residential life

[edit]The campus has fourteen residence halls, the newest of which opened in spring 2007. As of 2024, there are a total of fifteen on-campus residence halls, with eight located in North Campus and seven in South Campus.[184] Residence Hall Rates for the 2024–25 fall and spring terms vary across eleven different rates, ranging from the lowest rate of $13,504 to the highest rate of $20,447, each corresponding to different room types.[185] On-campus housing can hold more than 7,100 students.[186] Jester Center is the largest residence hall with its capacity of 2,945.[187] Academic enrollment exceeds the on-campus housing capacity; as a result, most students must live in private residence halls, housing cooperatives, apartments, or with Greek organizations and other off-campus residences. University Housing and Dining, which already has the largest market share of 7,000 of the estimated 27,000 beds in the campus area, plans to expand to 9,000 beds.[188]

Greek life

[edit]The University of Texas at Austin is home to an active Greek community. Approximately 14 percent of undergraduate students are in fraternities or sororities.[189] With more than 65 national chapters, the university's Greek community is one of the nation's largest.[189] These chapters are under the authority of one of the school's six Greek council communities, Interfraternity Council, National Pan-Hellenic Council, Texas Asian Pan-Hellenic Council, Latino Pan-Hellenic Council, Multicultural Greek Council and University Panhellenic Council.[190] Other registered student organizations also name themselves with Greek letters and are called affiliates. They are not a part of one of the six councils but have all of the same privileges and responsibilities of any other organization.[191] Most Greek houses are west of the Drag in the West Campus neighborhood.

Media

[edit]Students express their opinions in and out of class through periodicals including Study Breaks magazine, Longhorn Life, The Daily Texan (the most award-winning daily college newspaper in the United States),[192] and the Texas Travesty. Over the airwaves students' voices are heard through Texas Student Television (K29HW-D) and KVRX Radio.

The Computer Writing and Research Lab of the university's Department of Rhetoric and Writing also hosts the Blogora, a blog for "connecting rhetoric, rhetorical methods and theories, and rhetoricians with public life" by the Rhetoric Society of America.[193]

Traditions

[edit]

Traditions at the University of Texas are perpetuated through several school symbols and mediums. At athletic events, students frequently sing "Texas Fight", the university's fight song[194] while displaying the Hook 'em Horns hand gesture[195]—the gesture mimicking the horns of the school's mascot, Bevo the Texas Longhorn.

Smokey the Cannon

[edit]

The University of Texas is also represented by the Texas Cowboys, who maintain Smokey, the University's replica 1,200-pound Civil War artillery cannon.[196][197][198]

Athletics

[edit]The University of Texas offers a wide variety of varsity and intramural sports programs.

Varsity sports

[edit]

The university's men's and women's athletics teams are nicknamed the Longhorns. Texas has won 50 total national championships,[199] 42 of which are NCAA national championships.[200]

The football team experienced its greatest success under coach Darrell Royal, winning three national championships in 1963, 1969, and 1970. It won a fourth title under head coach Mack Brown in 2005 after a 41–38 victory over previously undefeated Southern California in the 2006 Rose Bowl.

The university's baseball team has made more trips to the College World Series (35) than any other school, and won championships in 1949, 1950, 1975, 1983, 2002, and 2005.[201]

The Texas Longhorns men’s basketball has qualified for the NCAA Final Four three times and achieved 28 conference championships and 38 total appearances in the NCAA tournament.[202]

Rick Barnes led the Texas Longhorns men's basketball from 1998 to 2015. Under his leadership, the team achieved 16 NCAA Tournament appearances, including a Final Four appearance in 2003.[203]

Shaka Smart coached the Texas Longhorns men's basketball from 2015 to 2021. While at UT Austin, Smart's teams made 3 NCAA Tournament appearances.[204]

Additionally, the university's men's and women's swimming and diving teams lay claim to sixteen NCAA Division I titles, with the men's team having 13 of those titles, more than any other Division 1 team.[205] The swim team was first developed under Coach Tex Robertson.[206]

On June 12, 2020, UT student-athletes banded together with their #WeAreOne statement on Twitter. Among the list of changes included: renaming certain campus buildings, replacing statues, starting outreach programs, and replacing "The Eyes of Texas". UT Interim President Jay Hartzell released a statement on July 13, 2020, announcing the changes to be implemented in light of these demands from UT student-athletes. Hartzell said the university would make a multi-million dollar investment to programs that recruit, retain and support Black students; rename the Robert L. Moore Building as the Physics, Math and Astronomy Building; honor Heman M. Sweatt in numerous ways, including placing a statue of Sweatt near the entrance of T.S. Painter Hall; honor the Precursors, the first Black undergraduates to attend the University of Texas at Austin, by commissioning a new monument on the East Mall; erect a statue for Julius Whittier, the Longhorns' first Black football letterman, at DKR-Texas Memorial Stadium; and more. However, one of the most controversial topics on the list – replacing "The Eyes of Texas" as UT's alma mater – remained untouched.[207]

- Further information: Horns Illustrated, print and digital university athletics publication.

Notable people

[edit]Faculty

[edit]In the fall of 2016, the school employed 3,128 full-time faculty members, with a student-to-faculty ratio of 18.86 to 1. These include[208][209] winners of the Nobel Prize, the Pulitzer Prize, the National Medal of Science, the National Medal of Technology, the Turing Award, the Primetime Emmy Award, and other various awards.[210] Nine Nobel Laureates are or have been affiliated with the University of Texas at Austin. Research expenditures for the university exceeded $679.8 million in fiscal year 2018.[211][212]

Alumni

[edit]Texas Exes is the official University of Texas alumni organization. The Alcalde, founded in 1913 and pronounced "all-call-day", is the university's alumni magazine.

Alumni in government

[edit]At least 15 graduates have served in the U.S. Senate or U.S. House of Representatives, including Lloyd Bentsen '42, who served in both Houses.[213] Presidential cabinet members include former U.S. Secretaries of State Rex Tillerson '75, and James Baker '57,[214] former U.S. Secretary of Education William J. Bennett, and former U.S. Secretary of Commerce Donald Evans '73. Former First Lady Laura Bush '73 and daughter Jenna '04 both graduated from Texas,[215] as well as former First Lady Lady Bird Johnson '33 & '34 and her eldest daughter Lynda.

In foreign governments, the university has been represented by Fernando Belaúnde Terry '36 (42nd President of Peru) and by Abdullah al-Tariki (co-founder of OPEC). Additionally, the Prime Minister of the Palestinian National Authority, Salam Fayyad, graduated from the university with a PhD in economics. Tom C. Clark '21, Law '22, served as United States Attorney General from 1945 to 1949 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1949 to 1967.

Alumni in academia

[edit]Alumni in academia include the Nobel Prize-winning immunologist James P. Allison, and the Nobel Prize-winning hematologist E. Donnall Thomas. Additional alumni include 26th president of The College of William & Mary Gene Nichol '76, the 10th president of Boston University Robert A. Brown '73 & '75,[216] and the 8th president of the University of Southern California John R. Hubbard. The university also graduated Alan Bean '55, the fourth man to walk on the Moon.

Alumni in business

[edit]Alumni who have served as business leaders include former Secretary of State and former ExxonMobil Corporation CEO Rex Tillerson '75, Dell founder and CEO Michael Dell, Morton Meyerson (name sake of the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center) and Gary C. Kelly, a former Southwest Airlines CEO.

Alumni in literature and journalism

[edit]In literature and journalism, the school boasts over 25 Pulitzer Prizes credited to alumni and faculty members,[217] including Gail Caldwell and Ben Sargent '70. Walter Cronkite, the former CBS Evening News anchor once called the most trusted man in America, attended the University of Texas at Austin, as did CNN anchor Betty Nguyen '95. Alumnus J. M. Coetzee also received the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature. Novelist Raymond Benson ('78) was the official author of James Bond novels between 1996 and 2002, the only American to be commissioned to pen them. Donna Alvermann, a distinguished research professor at the University of Georgia, department of education also graduated from the University of Texas, as did Wallace Clift ('49) and Jean Dalby Clift ('50, Law '52), authors of several books in the fields of psychology of religion and spiritual growth. Notable alumni authors also include Kovid Gupta ('2010), author of several bestselling books, Ruth Cowan Nash ('23), America's first woman war correspondent, and Alireza Jafarzadeh, author of "The Iran Threat: President Ahmadinejad and the Coming Nuclear Crisis" and television commentator ('82, MS).[citation needed] Although expelled from the university, former student and The Daily Texan writer John Patric went on to become a noted writer for National Geographic, Reader's Digest, and author of 1940s best-seller Why Japan was Strong.[218][citation needed]

Alumni with Fulbright Scholarships

[edit]University of Texas at Austin alumni also include 112 Fulbright Scholars,[219] 31 Rhodes Scholars,[219] 28 Truman Scholars,[220] 23 Marshall Scholars,[219] and nine astronauts.[221]

Alumni in music and entertainment

[edit]Several musicians and entertainers attended the university. Janis Joplin, the American singer posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame who received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, attended the university,[222] as did February 1955 Playboy Playmate of the Month and Golden Globe recipient Jayne Mansfield.[223] Composer Harold Morris is a 1910 graduate. Noted film director, cinematographer, writer, and editor Robert Rodriguez is a Longhorn, as are actors Eli Wallach and Matthew McConaughey, the latter of which now teaches a class at the university.[224] Founding members of psychedelic rock band The Bright Light Social Hour Jackie O'Brien and Curtis Roush both received master's degrees from the university in 2009 while completing their debut self-titled album.[225]

Kendall Ross Bean completed his Master of Music Degree in Piano Performance in 1982. As a master piano rebuilder and concert pianist, Bean first performed on a piano he rebuilt in one of the first classical music videos to be broadcast across the United States on the A&E Network which in 1985 had 18 million cable viewers. This broadcast coincided with MTV emerging as a medium for record production companies to use music videos to promote the albums of Rock and Pop stars. The novelty of a classical music video featuring a solo pianist and the inside view of piano hammers hitting strings, contrasted to the high production rock music videos caught media attention from coast to coast. The video was titled: Kendall Ross Bean: Chopin Polonaise in A Flat.

Karen Earle Lile, niece of Tony Terran, received her Bachelor of Arts Degree with Highest Honors in English in 1982. She is the Art Director/Executive Producer for the USPS Building Bridges Special Postal Cancellation Series and a Talk Show host for Sail Sport Talk on Sports Byline USA, a record producer [226][227] at Fantasy Studios and the historian who discovered the provenance of the Lost Lennon piano,[228] afterwards known as the Lennon-Ono-Green-Warhol piano.[229]

Robert Rodriguez dropped out of the university after two years to pursue his career in Hollywood, but completed his degree from the Radio-Television-Film department on May 23, 2009. Rodriguez also gave the keynote address at the university-wide commencement ceremony. Radio-Television-Film alumni Mark Dennis and Ben Foster took their award-winning feature film, Strings, to the American film festival circuit in 2011. Web and television actress Felicia Day and film actress Renée Zellweger attended the university. Day graduated with degrees in music performance (violin) and mathematics, while Zellweger graduated with a BA in English. Writer and recording artist Phillip Sandifer graduated with a degree in history. Michael "Burnie" Burns is an actor, writer, film director and film producer who graduated with a degree in computer science.[230] He, along with graduate Matt Hullum,[230] also founded the Austin-based production company Rooster Teeth, that produces many hit shows, including the award-winning Internet series, Red vs. Blue. Farrah Fawcett, one of the original Charlie's Angels, left after her junior year to pursue a modeling career. Actor Owen Wilson and writer/director Wes Anderson attended the university, where they wrote Bottle Rocket together, which became Anderson's first feature film. Writer and producer Charles Olivier is a Longhorn. So too are filmmakers and actors Mark Duplass and his brother Jay Duplass, key contributors to the mumblecore film genre. Another notable writer, Rob Thomas graduated with a BA in history in 1987 and later wrote the young adult novel Rats Saw God and created the series Veronica Mars. Illustrator, writer and alum Felicia Bond[231] is best known for her illustrations in the If You Give... children's books series, starting with If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. Taiwanese singer-songwriter, producer, actress Cindy Yen (birth name Cindy Wu) graduated with double degrees in music (piano performance) and broadcast journalism in 2008. Noted composer and arranger Jack Cooper received his D.M.A. in 1999 from the University of Texas at Austin in composition and has gone on to teach in higher education and become known internationally through the music publishing industry. Actor Trevante Rhodes competed as a sprinter for the Longhorns and graduated with a BS in Applied Learning and Development in 2012. In 2016, he starred as Chiron in the Academy Award- and Golden Globe-winning film Moonlight.

Alumni in sports

[edit]Many alumni have found success in professional sports. Legendary pro football coach Tom Landry '49 attended the university as an industrial engineering major but interrupted his education after a semester to serve in the United States Army Air Corps during World War II. Following the war, he returned to the university and played fullback and defensive back on the Longhorns' bowl-game winners on New Year's Day of 1948 and 1949. Seven-time Cy Young Award-winner Roger Clemens entered the MLB after helping the Longhorns win the 1983 College World Series.[232] NBA MVP and four-time scoring champion Kevin Durant entered the 2007 NBA draft and was selected second overall behind Greg Oden, after sweeping National Player of the Year honors, becoming the first freshman to win any of the awards. After becoming the first freshman in school history to lead Texas in scoring and being named the Big 12 Freshman of the Year, Daniel Gibson entered the 2006 NBA draft and was selected in the second round by the Cleveland Cavaliers. In his one year at Texas, golfer Jordan Spieth led the University of Texas Golf club to the NCAA Men's Golf Championship in 2012 and went on to win The Masters Tournament three years after leaving the university.[233] Several Olympic medalists have also attended the school, including 2008 Summer Olympics athletes Ian Crocker '05 (swimming world record holder and two-time Olympic gold medalist) and 4 × 400 m relay defending Olympic gold medalist Sanya Richards '06.[234][235] Mary Lou Retton (the first female gymnast outside Eastern Europe to win the Olympic all-around title, five-time Olympic medalist, and 1984 Sports Illustrated Sportswoman of the Year) also attended the university.[236] Garrett Weber-Gale, a two-time Olympic gold medalist, and world record-holder in two events, was a swimmer for the school. Also an alumnus is Dr. Robert Cade, the inventor of the sports drink Gatorade. In big, global philanthropy, the university is honored by Darren Walker, president of Ford Foundation. 2022 and 2024 Masters Tournament champion, Scottie Scheffler '18, attended the university, where he was an All-American Golfer for the Longhorns.

Other notable alumni

[edit]Other notable alumni include prominent businessman Red McCombs, Diane Pamela Wood, the first female chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, chemist Donna J. Nelson, and neuroscientist Tara Spires-Jones. Also an alumnus is Admiral William H. McRaven, credited for organizing and executing Operation Neptune's Spear, the special ops raid that led to the death of Osama bin Laden.[237] Oveta Culp Hobby, the first woman to earn the rank of a colonel in the United States Army, first commanding officer and director of the Women's Army Corps, first secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare attended the university as well. Erika Thompson is a well-known beekeeper.

- Notable alumni of UT Austin

-

James P. Allison, Nobel Prize-winning immunologist

-

Tom C. Clark, Attorney General and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

-

J. M. Coetzee, novelist and Nobel laureate

-

Kevin Durant, 14-time NBA All-Star

-

Matthew McConaughey, Academy Award-winning actor

-

Jordan Spieth, professional golfer

-

E. Donnall Thomas, Nobel Prize-winning hematologist

-

Rex Tillerson, Secretary of State

-

Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist

-

Owen Wilson, actor

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Disciplina Praesidium Civitatis is a Latinization of the quotation by Mirabeau B. Lamar that "The cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy."

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ "UT Seal". Texas Exes. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ Battle, William James (December 2, 2015) [June 15, 2010]. "The University of Texas at Austin". Handbook of Texas (online ed.). Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ "UT Seal". Ex-Students Association of The University of Texas. n.d. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ a b "Smartbook" (PDF). University of Texas System. May 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "U.S. and Canadian 2023 NCSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2023 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY22 to FY23, and FY23 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student" (XLSX). National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO). February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "McCombs Business Dean Hartzell named interim president of UT Austin". The University of Texas System. April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Facts & Figures | the University of Texas at Austin".

- ^ "Fast facts 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "UT Austin Enrolls Largest-Ever Student Body, Sets All-Time Highs for Graduation Rates". September 22, 2022.

- ^ "IPEDS-University of Texas at Austin".

- ^ "Colors | Brand | The University of Texas". Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ Cobb, David; Dodd, Dennis (July 30, 2021). "Texas, Oklahoma join SEC: Longhorns, Sooners accept invitations as Big 12 powers begin new wave of realignment". CBS Sports.

- ^ "Facts & Figures | The University of Texas at Austin". www.utexas.edu. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "UT exceeds $1 billion in research expenditures".

- ^ "Texas Athletics completes Tokyo Olympics with 9 total medals, including 5 gold". University of Texas Athletics. August 9, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Sons of Dewitt County, The Constitution of Coahuila and Texas". Wallace L. McKeehan. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836)". Tarlton Library, Jamail Center for Legal Research, School of Law, University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Laws of Texas, 1822–1897 Volume 4". H.P.N Gammel of Austin. 1898. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Laws of Texas, 1822–1897 Volume 4". H.P.N Gammel of Austin. 1898. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Matthews, Charles Ray (2006). The Early Years of the Permanent University Fund from 1836 to 1937. UMI (UMI Number 3284727). p. 32.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1876)". Tarlton Library, Jamail Center for Legal Research, School of Law, University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "The Laws of Texas, 1822–1897 Volume 9". H.P.N Gammel of Austin. 1898. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Lane, John J. (1891). History of the University of Texas: Based on Facts and Records. Henry Hutchings, Texas State Printer. p. 267.

- ^ "History of the UT System Board of Regents". The University of Texas System. June 18, 2018. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Silverthorne, Elizabeth (1982). Ashbel Smith of Texas: Pioneer, Patriot, Statesman, 1805–1886. Texas A&M University Press. p. 219.

- ^ "State University Notice". Austin American_Statesman. September 15, 1883. p. 4.

- ^ Collections, Special. "Tarlton Law Library: Exhibit – UT School of Law Buildings in Photographs: Old Main". tarlton.law.utexas.edu. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Nicar, Jim (March 8, 2019). "Main Building". The UT History Corner. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Steen, Ralph W. (February 24, 2016) [June 12, 2010]. "Ferguson, James Edward". Handbook of Texas (online ed.). Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ Smith, Julia Cauble (June 15, 2010). "Santa Rita Oil Well". Handbook of Texas (online ed.). Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ "Legislative Reference Library of Texas, HB 368, 42nd Regular Session" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Texas State Education Code, Title 3, Subtitle C, Chapter 66.02". Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Association of American Universities". Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Administration in World War II". HyperWar Foundation. 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ Nicar, Jim (June 4, 2014). "The University Learns of D-Day". The UT History Corner. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Price, Asher. "Memo by secret memo, the University of Texas kept segregation alive into the 1960s". Mother Jones. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Leila Ruiz (April 4, 2014). "UT's first black students faced significant discrimination on the long road to integration". The Daily Texan. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Cary D. Wintz, "The Struggle for Dignity: African Americans in Twentieth-Century Texas" in Twentieth-Century Texas: A Social and Cultural History (eds. John Woodrow Storey & Mary L. Kelley. University of North Texas Press, 2008).

- ^ Price, Asher (September 19, 2019). "A Secret 1950s Strategy to Keep Out Black Students". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Tretter, Elliot M. (2016). Shadows of a Sunbelt City: The Environment, Racism, and The Knowledge Economy in Austin. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. pp. 46–50. ISBN 978-0-8203-4489-8.

- ^ "Legislative Reference Library of Texas, HB 222, 60th Regular Session". Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ a b Slattery, Patrick (2006). "Deconstructing Racism One Statue at a Time: Visual Culture Wars at Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin". Visual Arts Research. 32 (2): 28–31. JSTOR 20715415.

- ^ The University of Texas at Austin Visitor's Guide, 2008, p. 21

- ^ "UT Austin AT&T Executive Education Center". Lake Flato. July 29, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "UT Austin Shooting Rampage Ends Tragically in the Library". American Libraries Magazine. September 28, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Chinese province placed on UT-Austin's restricted travel list after coronavirus outbreak". KXAN Austin. January 28, 2020. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Proctor, Clare (April 4, 2020). "Hundreds of UT-Austin students went to Cabo San Lucas for spring break. Nearly 50 have coronavirus". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Justin, Raga (July 30, 2020). "After voluntarily publishing its data, UT-Austin now has the unwelcome distinction of leading U.S. colleges in COVID-19 cases". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "UT Austin Custodial Staff Member Dies from COVID-19 Complications". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. July 8, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Price, Asher. "Amid COVID-19 spike, UT to go virtually all virtual through January". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Burkhart, Ross (March 11, 2024). "UT Austin Reinstates Standardized Test Scores in Admissions". UT News. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Boyette, Kaanita Iyer, Chris (June 15, 2023). "Texas governor signs bill to ban DEI offices at state public colleges | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Creighton, Brandon (March 26, 2024). "Senator Brandon Creighton Announces Oversight on Senate Bill 17 Implementation". The Texas State Senate. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Alonso, Johanna (April 4, 2024). "UT Austin Closes Former DEI Division". Inside Higher Ed.

- ^ Nietzel, Michael T. "University Of Texas Laying Off Staff To Comply With State's DEI Ban". Forbes. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "UT Austin lays off around 60 staffers to comply with Texas DEI ban". KUT Radio, Austin's NPR Station. April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "April 15, 2024, Faculty Council Meeting Transcript" (PDF). The University of Texas at Austin Faculty Council. p. 15. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ "Spring 2024 Organizational Restructuring". The University of Texas at Austin | Human Resources. April 2, 2024. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Aguasvivas, Arleen; Chan, Melissa; Essamuah, Zinhle (February 7, 2024). "Stabbing of Palestinian American man in Texas was motivated by bias, police say". NBC News. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ Oladipo, Gloria (February 8, 2024). "Stabbing of Palestinian American in Texas a hate crime, police say". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ "Stabbing of Palestinian American near the University of Texas meets hate crime standard, police say". Associated Press. February 7, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ "Austin police say West Campus attack meets hate crime definition". KVUE. February 7, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ Ramkissoon, Jaclyn; Jones, Abigail; Washington, Jala; Huey, Dalton (February 6, 2024). "APD: Committee says stabbing near UT campus meets definition of hate crime". KXAN-TV. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ Schnitker, Andrew (April 23, 2024). "Man indicted in UT West Campus stabbing of Palestinian American". KXAN-TV. Archived from the original on May 20, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Kepner, Lily; Moreno-Paz, Bianca (April 25, 2024). "Live: UT-Austin professors plan protest with students, PSC calls for Hartzell's resignation". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Bushard, Brian. "Texas Troopers Arrest University Of Texas Students During Protest". Forbes. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ "Campus protests live update: Encampments continue at Columbia as police descend on protesters at University of Texas at Austin". NBC News. April 24, 2024. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ The Daily Texan [@thedailytexan] (April 25, 2024). "BREAKING: UT President Jay Hartzell's messages with a state senator and the UT System Chancellor reveal he requested additional help from DPS at yesterday's protest because "our police force couldn't do it alone," according to messages obtained by The Austin American-Statesman" (Tweet). Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Chandler, Ryan [@RyanChandlerTV] (April 25, 2024). "It was President Hartzell himself who called in DPS to respond to the protests yesterday, UT tells me. "That was President Hartzell. That was President Hartzell. Along with his leadership team and UT System Board of Regents Chairman Kevin Eltife," Comms Director Mike Rosen said" (Tweet). Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Dey, Sneha; Mohamed, Ikram; Xia, Annie; Melhado, William (April 24, 2024). "Police arrest more than two dozen pro-Palestine protesters on UT-Austin campus amid tense standoff". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Leija, Ren (April 24, 2024). "Hundreds of UT Austin students, faculty gather on campus for pro-Palestinian protest". The Daily Texan.

- ^ Irwin, Lauren (April 24, 2024). "Abbott says pro-Palestine protesters at UT Austin 'belong in jail'". The Hill.

- ^ a b Downen, Robert (April 25, 2024). "UT-Austin faculty criticizes response to pro-Palestine walkout as students plan new protest". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Velez, Abigail (April 24, 2024). ""This was supposed to be peaceful": Dozens detained at UT Austin protest". CBS Austin. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ "At least 50 arrested at pro-Palestine protests on UT Austin campus". KVUE Austin. April 24, 2024. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ "University of Texas Palestine protest leads to more than 30 arrests, including FOX 7 photographer". FOX 7 Austin. April 25, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Paul, Kari (April 24, 2024). "Fox journalist among dozens arrested at Texas university as protests swell". The Guardian. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Weber, Andrew (April 25, 2024). "Charges dismissed against 46 arrested during pro-Palestinian protest at UT Austin". KUT News.

- ^ Robertson, Nick (April 25, 2024). "Texas prosecutor declines to charge student protesters arrested at UT Austin". The Hill. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Weber, Andrew (April 26, 2024). "Charges dropped against all 57 pro-Palestinian demonstrators arrested on UT campus". KUT News. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Grant, Matt (April 25, 2024). "Press freedom advocates want change following Austin photojournalist protest arrest". KXAN-TV. Archived from the original on April 26, 2024. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Elbein, Saul (April 25, 2024). "Texas Gov. Abbott faces backlash after mass arrest at UT Austin pro-Palestine protest". The Hill. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Downen, Robert; Mohamed, Ikram; Melhado, William (April 25, 2024). "Faculty petition to hold no-confidence vote in UT-Austin president after protest response". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Perry, Nick; Vertuno, Jim; Coronado, Acacia (April 24, 2024). "Dozens arrested on California campus after students in Texas detained as Gaza war protests persist". AP News.

- ^ Monacelli, Steven [@stevanzetti] (April 25, 2024). "NEW: UT Austin released "protest rules" that say "individuals may not come to campus without authorization," which is in direct contradiction to a video they published 6 months ago that says members of the public can "come to campus at any time and engage in demonstrations."" (Tweet). Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ McGlinchy, Audrey; McGaughy, Lauren (April 26, 2024). "UT Austin changes message again, says arrested students will be allowed on campus for any reason". KUT News. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Chandler, Ryan [@RyanChandlerTV] (April 25, 2024). "Breaking: UT's Palestine Solidarity Committee receives an "interim suspension," an internal memo obtained by @KXAN_News states. UT leaders say they made attempts to meet with organizers beforehand" (Tweet). Retrieved April 25, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Pauda, Erica; Jones, Abigail; Schnitker, Andrew (April 30, 2024). "Monday's UT protest arrest cases remain active, County Attorney says". KXAN. Archived from the original on May 2, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ McGlinchy, Audrey (July 31, 2024). "UT Austin committee says administrators violated own rules when handling protests". KUT News. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ The Main Building Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The University of Texas. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ University approves new policy for lighting The Tower Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine On Campus. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ [1] Archived August 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ A few facts about Knicker Carillon Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine On Campus. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ "Tower tours". The Texas Union. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ "Statistical Overview of the Library Collections, 2007". Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2011. The University of Texas Libraries. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ The Gutenberg Bible at the Ransom Center Archived October 16, 2002, at the Wayback Machine Harry Ransom Center. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ "Blanton Museum of Art Poised to Become Largest University Museum in the United States". Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Blanton Museum of Art: About". Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ Hall, Sid Richardson (December 16, 2015). "Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection". Poets & Writers. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Norsworthy, Kent (September 29, 2016). "Digital Resources: LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, University of Texas at Austin". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.81. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9.

- ^ Story, Wesley (August 7, 2017). "Alumnus reflects on illicit UT tunnel adventures". The Daily Texan. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "Tunneling for Truth: the Myth Explained". The Daily Texan. 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Tynan (February 12, 2006). "The Secret Tunnels Under UT". Archived from the original on February 14, 2006.

- ^ Nuclear Engineering Teaching Lab Archived September 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Nuclear and Radiation Engineering Program. Retrieved February 10, 2006.

- ^ Collier, Bill. Reactor draws safety questions. Austin American-Statesman. December 15, 1989.

- ^ "Gates Computer Science Complex and Dell Hall Open". Department of Computer Science at UT Austin. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ "Belo Center for New Media Opens". College of Communication. October 20, 2012. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ "Student Activity Center Opens for Business". The Daily Texan. January 18, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "UT Shuttles". Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Colleges and Academic Units The University of Texas. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- ^ "Degrees Conferred Information, 2009–2010 Academic Year" (PDF). The University of Texas Office of Institutional Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2012.

- ^ "UT College of Liberal Arts". liberalarts.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "UT College of Liberal Arts". liberalarts.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "TIP Scholars". Utexas.edu. Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2021–2022". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2016–2017". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Standardized Testing Policy FAQs". admissions.utexas.edu. The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". admissions.utexas.edu. The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Thomas, G. Scott. "The colleges in the South with the toughest admission standards – The Business Journals". Bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ "The University of Texas at Austin to Automatically Admit Top 8 Percent of High School Graduates for 2011". Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Admission: Undergraduate Admission". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010.

- ^ "University of Texas-Austin". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 8, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "The University of Texas at Austin 2017–2018 Common Data Set, Part C". The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ "PDF Common Data Set Reports – Institutional Reporting, Research and Information Systems". reports.utexas.edu. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ "National Merit Scholarship Corporation 2019–20 Annual Report" (PDF). National Merit Scholarship Corporation. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2020–2021". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2019–2020". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2018–2019". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "University of Texas at Austin Common Data Set 2017–2018". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ a b "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.